This is a topic I’ve wanted to write about for a while, and I will dedicate more time (and deeper research) to it if I ever write a book or graphic novel or something like that. For now, though, I want to briefly examine a fascinating component of global foodways: colonialism. How did the establishment of colonies worldwide by (mostly) European powers affect the cuisine of the colonized, and when did that process actually work in reverse?

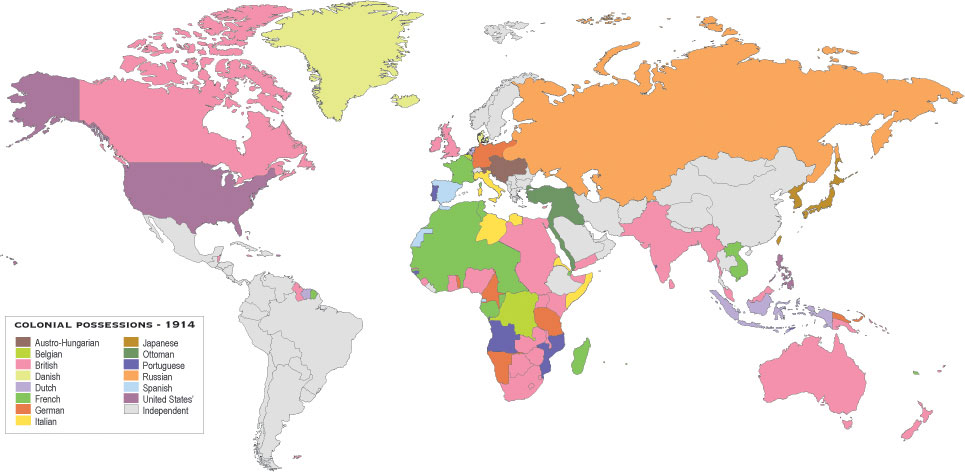

Let’s look at a colonial map of the world for a bit of background (this one shows the world in 1914):

I won’t bore you with deep colonial history, but from the map we can see that the continent of Africa was pretty well carved up by the Europeans after the so-called “Scramble for Africa” between 1881 and 1914. The British had, of course, made their way around the Horn of Africa and made inroads in South Asia as well as the South Pacific. The French had an outpost in Southeast Asia, the Dutch were present throughout Indonesia, and the Portuguese owned parts of Southern Africa as well as a blip in India, Goa. The list, of course, goes on — the Belgians in the Congo, Italy in North Africa and Somalia, the Germans in Southern Africa.

This global conquest for land, resources, and power significantly changed the world, overwhelmingly for the worse: death, destruction, slavery, state failure, social injustice, and racism are just some of the consequences of colonialism. The seriousness of the destructive history of New Imperialism cannot be overstated. We are still dealing with fallout today.

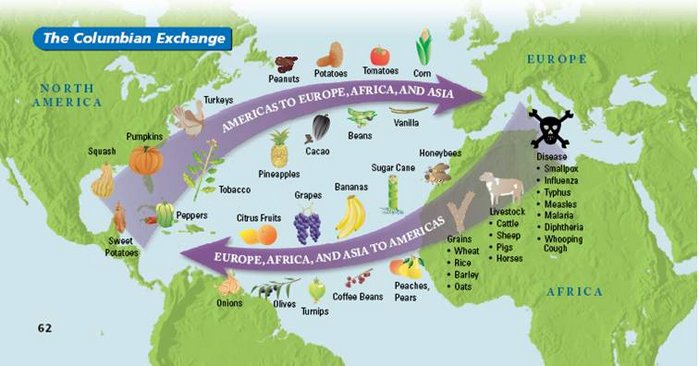

Our investigation, though, is of a less negative piece of colonialism: its longterm effects on cuisine. Global migration has affected food throughout history (how did potatoes get to Ireland, tomatoes to Italy, and chilis to India?), and the spread of Europeans and Continental tastes had a significant impact on their subjugated peoples’ cuisines.

So, here are a few examples for a bit richer understanding of this idea; from single dishes to entire amalgamate cuisines. Many parts of world history and human migrations can be understood from examples like these; like raw ingredients that compose a dish, components from many cultures and time periods go into making a cuisine writ large. Looking critically at some of these ingredients, these building blocks, allows us to understand colonial history and migratory patterns, as well as politics, war, and peace.

Bánh mì – While the Vietnamese phrase “bánh mì” simply refers to bread, it has come to signify a style of sandwich popular worldwide. Traditionally, a bánh mì consists of a baguette filled with pork liver pâté, sliced ham, pickled vegetables, jalapeños, and cilantro. This is a classic mash-up of a colonial cuisine. It was once called a “French sandwich” in colonial French Indochina (now Vietnam) due to its original composition of pâté, ham, cornichons, and butter on a baguette. Over the years, the sandwich started to include traditional Vietnamese ingredients — the spicy peppers, the cilantro — and modified versions others, like replacing the cornichons with pickled daikon and the butter with fish sauce aioli. The sandwich has gained international popularity, traveling with Vietnamese diaspora populations worldwide, and has retained its place as delicious, quick street food in Vietnam. This is a true culinary alloy, one intricately linked to colonial history.

Baasto – Somalia is a great trade crossroads, and its cuisine reflects a history of influence by traders from India, East Africa, and the Middle East. Its colonizer, though, was Italy, and with the Italians came pasta — spaghetti. Or as it’s known in Somali, Baasto. Baasto is a sort of de facto national dish of Somalia, and is served with a thick tomato sauce, sometimes doctored with decidedly non-Italian ingredients like cilantro, tamarind, and Xawaash, a sweet-spicy spice blend. The dish is recognizably Italian, but distinctly Somali in taste. (Interestingly, the Italian influence in the region also led to a profusion of imported espresso makers which, when combined with the incredible coffees from Ethiopia’s regions of Sidamo, Yirgacheffe, and Harar make for some fine cups of coffee. I discovered this while living in Hargeisa, Somaliland, when I discovered Purple Coffee Corner on my walk to work: it had a vintage espresso maker and freshly roasted beans from neighboring Ethiopia.)

Goan Cuisine – A tiny colony on the southwest coast of India, Goa was settled by the Portuguese in the 16th century, who brought with them potatoes, chilis, tomatoes, and more from their colony in Brazil. From the famous pork blood and offal stew Sorpotel, known as Sarapatel in Brazil, to Feijoada, a stew of beef or pork with beans which can be found in Brazil, Angola, Macau, and Mozambique, the cuisine of Catholic Goa is intricately imprinted by Portuguese culinary traditions and imports. Like the wonders of tectonic plate shifts, which allow us to see geological similarities and paleontological brethren thousands of miles apart, we can see culinary kin with slight regional variations on opposites sides of the earth, due to the maritime explorations and colonial exploits of the Portuguese.

This pollination, of course, doesn’t just go one way. Some European cuisines were far more deeply affected by colonial immigration than vice versa. It is well-known that Indian and Pakistani food are the best culinary options in the United Kingdom, and it was once proposed in the UK Parliament that the city of Glasgow be given EU Protected Designation of Origin status as the birthplace of Chicken Tikka Masala. The Dutch colonized Indonesia, which led to an incredible Indonesian food scene in Amsterdam; notably, Rijsttaffel (“rice table”) restaurants have flourished in the Dutch capital, offering dozens of small side dishes served with rice. This was a Dutch invention, as the colonizers wanted to fill their tables with exotic fare; when they left, the tradition retreated as well and exists mostly in the Netherlands.

There are more questions here to answer than I have time or space for, and I’m sure your energy is flagging by now (and your appetite is rising!) Namely: in which cases did a colonial power’s cuisine trickle into the local mainstream, and when did that stream reverse? Why are some cuisines more “sticky” than others — the Portuguese have spread many more of their culinary traditions than the British, for example. I’m also drawn to learn more about the conflict and slavery that underlies much chocolate and coffee consumption worldwide — the main reason Belgian chocolate is world renowned is the exploitative relationship Belgian King Leopold II had with the Congo. And finally, another fascinating facet of this is a non-national angle of global colonization: corporate culinary imperialism. This is mostly an American-led phenomenon, the export of American fast food chains and subsequent adoption of American diets globally. McDonald’s and KFC have de facto embassies in more than 100 countries. Starbucks has raised its green and white mermaid in 63 countries. Coca-Cola claims to have their product in over 200 countries, which is even more than recognized by the United Nations.

These are all posts for another day. Now it’s time for a Bánh Mì and a coupe of French Champagne.

One Response

The Power of the WFP’s VoucherChef Project | Culinary Diplomacy

[…] ← Culinary Colonialism, or, Pour Quoi Bánh Mì? […]